This is the first piece of land acquired by Manu Manu Riforesta! thanks to the fundraising campaign. It is a small area of wetland with a thick elm wood – c.1 hectare (2.5 acres). It is a precious and rare ecosystem, designated a temporary (or seasonal) pond, protected under the European Habitat Project, Nature 2000, as a special area of conservation (SAC).

The SAC is called Padula Mancina. The biggest wetland in the southern part of the Paduli, it includes Fosso Padule Rotondo and the Stagno Canali, and has an area of 91 hectares (c.225 acres).

Why is this little ‘temporary pond’ of Manu Manu Riforesta! in the list of 26 ZSC in Apulia?

It is thanks to the discovery of hairy aquatic clover. What place will the Bosco Don Tommaso occupy in the agroforestation project, and what are the possible actions? “The role of man in the ecological processes that govern the temporary ponds is usually undervalued, if not completely unknown. The management of the temporary ponds presupposes a cultural process to which all – public administration, research bodies, associations and various professionals – can responsibly contribute.”

Of this and more the biologist and ecologist Leonardo Beccarisi writes further.

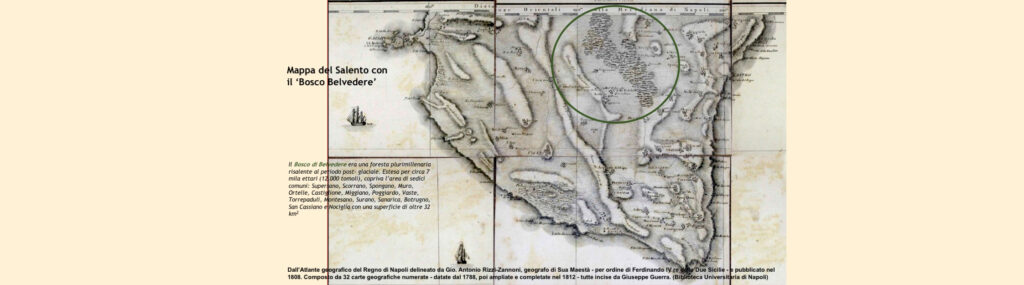

The temporary pond at Bosco Don Tommaso

Scientific study of the temporary pond at Bosco Don Tommaso has a short history. This began in 2009 with the discovery of a rare waterclover close to the Padula Mancina pond at Montesano Salentino. This note recounts the discovery of this species, of the setting up of the SAC Padula Mancina of which the Don Tommaso wood is a part, and of the ecological importance of temporary ponds.

The waterclover Marsilea strigosa

The waterclover Marsilea strigosa is a small perennial characterized by an underground creeping stem and by hairy leaves with laminae subdivided into four segments. Being of the fern family the plant does not produce flowers but reproduces itself through spores. The area of distribution is strictly Mediterranean and linked to the habitat of temporary ponds.

The presence of this species in Puglia has been documented in publications dating back to the 1800s (Fiori 1943). It was reported in the province of Foggia, the Gulf of Taranto and the Alimini Lakes, but because of the lack of subsequent observations the extinction of this species in Puglia was recently considered possible. It was a hypothesis also confirmed by the negative trend for this species in all of its distribution areas, including Europe (Bilz et al., 2011).

The principal cause of the general decline of the hairy aquatic clover is the transformation of its particular habitat. Drying up, canalization, and tillage have been occurring for decades causing damage to all the wetlands on the Mediterranean coast, and specially to the seasonal ones which, in brief, are among the most vulnerable aquatic ecosystems.

The establishment of two new SAC in the Salento for the conservation of the waterclover Marsilea strigosa

The Habitats Directive 92/43/CEE has as its objective the conservation of biodiversity in the European Union through a system of protected areas called Natura 2000 network. Identifying these areas is based on the presence of particular species and types of natural habitat on which the European Union places special interest. The waterclover Marsilea strigosa, given the risk of extinction it faces in Europe, has been included in the list of species of community interest according to the Habitats Directive.

When the scientific community considered the waterclover Marsilea strigosa to be extinct everywhere in Italy with the exception of Sardinia (Bartolucci et al., 2018), it was unexpectedly found in Puglia at Padula Mancina in the commune of Montesano Salentino (Accogli & Beccarisi, 2010). Not long after it was also found at the Lago del Capraro, between the communes of Soleto and Sternatia (Ernandes & Marchiori, 2012). Thus, it seemed the waterclover Marsilea strigosa had reappeared in Puglia after more than a century even if in different places than those previously reported. In reality, rather than a reappearance the new sightings were the result of a new and growing scientific interest in the seasonal wetlands of Puglia and an intensification of research on this theme in the last 15 years (Beccarisi et al., 2007; Alfonso et al., 2011).

In subsequent years, when periodic monitoring took place to evaluate the state of conservation of the habitats and the species of Natura 2000 network, new data on the two sites in the Salento was delivered to the European Union. This was decisive for launching, on the request of the European Union, a procedure to include the two new sites in Natura 2000 network. In fact, because the sites were not included in this protection system, it was not possible to set up special conservation measures for the waterclover Marsilea strigosa as planned by the Habitat Directive.

Thus, the Region of Puglia’s Parks & Biodiversity Conservation Service, with the scientific support of Bari University’s Botanic Garden Museum, drew up the proposal for the establishment of two Sites of Community Interest: Padula Mancina (IT9150035) and Lago di Capraro (IT9150036) for the conservation of the waterclover Marsilea strigosa (DGR no. 1596/2016). Following that the conservation measures already in place for the habitats and species of Natura 2000 network in Puglia (Regional Regulation no.16/2016) were extended to the two new sites (Regional Regulation no.12/2007). The designation of the two sites as SAC (Decree, 28 December 2018) made their inclusion in Natura 2000 network effective. The change of denomination is essential, given that it predisposes the sites to being identified by a management body and to the drawing up of a management plan, following an ongoing administrative procedure.

The Special Area of Conservation “Padula Mancina”

The Special Area of Conservation Padula Mancina (from now on referred to as a SAC) was identified according to two criteria of conservation ecology: the definition of a buffer area and the distribution of the risk.

The environmental conditions of the pond depend not only on the ecological processes inside it but also on the activities outside it. It is for this that the area of the SAC is larger than that of the pond in which the waterclover Marsilea strigosa is present, and includes an ample area of cultivated fields and uncultivated wetlands which have the role of buffer area.

The waterclover Marsilea strigosa plants are unique in this area and are distant from those in the Lago del Capraro, 30 km to the north. The inclusion in the SAC of extra nearby areas with similar ecological characteristics, even if they are not colonized by the species that is the object of conservation makes for a broad setting for protection that enables drawing up effective actions for reducing the risk of extinction of the species. For example, moving the plants from one site to the other is a possibly valid solution. For this reason, the SAC is made up of three separate but nearby areas: Padula Mancina in the commune of Montesano Salentino, the Stagno Canali in the commune of Miggiano and the pond at Bosco Don Tommaso in the commune of Ruffano. This last is reported in the ecological study attached to DGR no.1596/2016 as a Ditch at Palude Rotondo. The SAC has an area of 91 hectares (c.225 acres).

The habitat of Mediterranean temporary ponds

The three ponds in the SAC have similar hydrological characteristics. They are seasonal, which means they fill up in winter and dry out in summer. The water is exclusively rainwater and accumulates in the pond by surface runoff from the surrounding fields. These conditions create a particular type of natural habitat, Mediterranean temporary ponds, which are included in the types of habitat covered by the Habitats Directive.

The Mediterranean temporary ponds (Natura 2000 code: 3170*) are one of the habitats identified by the Habitats Directive as elements to which particular attention should be paid. Because of the worrying situation in which they are to be found, it is in fact necessary to predispose urgent conservation measures; in the terminology of the Directive, these are called priority habitats and occupy a special position in respect to all the other habitats of community interest.

The reasons for this particular attention to the Mediterranean temporary ponds lies in the fact that the seasonal humid areas are particularly vulnerable. Being of a modest size and drying out for part of the year, they are easily damaged and subject to transformation through ploughing, topping up, drainage, or if individuated as the terminal point for extensive hydraulic systems they can become permanently flooded hydraulic bodies. They are operations that have been widely performed not only in the past, as for example during the entire clear up of the last century, but also in recent times.

But what is so special about this type of habitat? It hosts species of vegetation and animals strongly adapted to live in perpetual alternation between two environmental conditions: winter flooding and summer drought. These species are typically Mediterranean and have an annual cycle. Most of the aquatic animals and algae reproduce in the flood period. During the period of drought, only a few perennial plants remain in vegetative form while most of the organisms die producing seeds, spores, quiescent buds, eggs and cysts, that is corpuscles of various types resistant to dehydration that deposit themselves in large quantities on the bottom of the pond; in this state they can be accidentally transported long distances by birds. The algae (such as the muskgrass) and the crustaceans (such as the branchiopods) produce forms of resistance which remain quiescent for the whole summer; plants (such as buttercups and water-starworts) produce seeds; the water ferns (such as quillworts and waterclovers) produce spores. These are extremely distinctive species, in many cases rare and at risk of extinction, which arrange themselves in a biological community that is very diverse and sensitive to the minimum environmental variation.

In the Bosco Don Tommaso pond the habitat of the Mediterranean temporary ponds is little extended but manifests characteristics that are nonetheless interesting. For example, present in the site is the Heliotropium supinum, a plant species whose area of distribution in Puglia is presumably in regression; the species is in fact noted only for the SAC and for another protected area in the region at the Laghi di Conversano in the province of Bari.

Management of the temporary ponds and of the species that colonise them is a delicate problem that needs to be addressed with competence. In the absence of adequate ecological knowledge, the risk is of taking actions with the intent to protect but that can in time reveal themselves to be destructive. For example, the role of man in the ecological processes that govern the temporary ponds is usually undervalued, if not entirely unknown. The sites in which the habitat occurs are frequently managed, or were historically managed, though traditional grazing.

Thus, like the steppe grasslands, which are a distinctive element of the Mediterranean landscape, the temporary ponds are also the result of a long-lasting interaction between the shepherd and resources of spontaneous weeds; a system of man/flocks/vegetation that evolved for centuries, if not even for thousands of years. This is an evident case in which restoring nature can be pursued above all through the restoration of the relationship between man and nature. The management of the temporary ponds presupposes, therefore, a cultural process to which all affiliated to public administration, research bodies, associations or to various professional bodies can contribute responsibly.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Accogli R., Beccarisi L. (2010) 178. Marsilea strigosa L. Puglia (D. Marchetti, Ed.). Ann Mus civ Rovereto, Sez : Arch, St, Sc nat 25 (2009):103–104.

Alfonso G., Belmonte G., Ernandes P., Zuccarello V. (2011) Stagni Temporanei Mediterranei in Puglia. Biodiversità e aspetti di un habitat poco conosciuto. Edizioni Grifo, Lecce.

Bartolucci F., Peruzzi L., Galasso G., Albano A., Alessandrini A., Ardenghi N.M.G., Astuti G., Bacchetta G., Ballelli S., Banfi E., Barberis G., Bernardo L., Bouvet D., Bovio M., Cecchi L., Di Pietro R., Domina G., Fascetti S., Fenu G., Festi F., Foggi B., Gallo L., Gottschlich G., Gubellini L., Iamonico D., Iberite M., Jiménez-Mejías P., Lattanzi E., Marchetti D., Martinetto E., Masin R.R., Medagli P., Passalacqua N.G., Peccenini S., Pennesi R., Pierini B., Poldini L., Prosser F., Raimondo F.M., Roma-Marzio F., Rosati L., Santangelo A., Scoppola A., Scortegagna S., Selvaggi A., Selvi F., Soldano A., Stinca A., Wagensommer R.P., Wilhalm T., Conti F. (2018) An updated checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosystems 152:179–303.

Beccarisi L., Medagli P., Mele C., Ernandes P., Marchiori S. (2007) Precisazione sulla distribuzione di alcune specie rare degli ambienti umidi della Puglia meridionale (Italia). Informatore Botanico Italiano 39:87–98.

Bilz M., Kell S.P., Maxted N., Lansdown R.V. (2011) European Red List of Vascular Plants. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

Ernandes P., Marchiori S. (2012) The rare water fern Marsilea strigosa Willd.: Morphological and anatomical observations concerning a small population in a Mediterranean temporary pond in Puglia. Plant Biosystems 146 suppl.:131–136.

Fiori A. (1943) Flora Italica Cryptogama. Pars V: Pteridophyta. Società Botanica Italiana, Firenze.